Whose "own": Part 2

Belonging, and cross-cultural sharing

This photo was taken during the summer of my PhD cohort. We are Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars from various countries, including the Philippines, Panama, Tasmania, and the Lakota Nation in the mid-west. Despite our differences in language, culture, and background, we are stronger together. However, there are many factors that complicate our ability to bring our strengths to the collective. For instance, the colonial project has attempted to separate many of my Indigenous friends from their languages and cultures, embedding a sense of shame in previous generations that are now incapable of passing on knowledge. Migration has also separated many of us from the places that shaped our names, stories, and ancestors. Various myths have been at work reinforcing the idea that we all bleed red, so it doesn’t matter where we come from. Unfortunately, these myths have not served to make us stronger in our shared humanity. They have made us less, not more.

But whose “own” are we? Where do we belong? Who are our people? Who lays claim to us? And what do we have to share when we are together? Many of us are searching for answers to these questions.

Always have a song you are ready to share.

When I was travelling in Aotearoa (New Zealand) in 2013, I was told to “always have a song you are ready to share.” The idea of exchanging songs was a beautiful means of connection. It is a way of sharing who you are and receiving a bit of who your hosts are. However, I had no idea what songs to sing. This isn’t karaoke; it is a cultural exchange. But what is my culture as an American immigrant to Canada with Scandinavian and German roots that were left behind at Ellis Island when our names were changed from Wolfenbarger to Spargur and Virkkula to Wilson?

There is an image in the book of Revelation about when people from “every tongue, tribe, and nation” will enter the throne room of God. When I experience the Grand Entry at a Pow Wow, I often think of this image. It reminds me that we are all connected, and that our differences should be celebrated, not feared.

There is an image in the book of Revelation about when people from “every tongue, tribe and nation” will enter the throne room of God. When I experience the Grand Entry at a Pow Wow, I often think, this is what it will be like when we enter the throne room of God at the end of time, in all the splendour, beauty, uniqueness and diversity of the cultures of the earth. But what will my contribution be? What will I wear? What songs will I sing? What dances to dance? What unique aspect of the image of God will I reflect as a part of the people to whom I belong?

For many Settler folks, we can run the risk of appropriating Indigenous cultures because we don’t know who we are. We don’t know the contribution that we make. We don’t know whose “own” we are.

So I am learning to joik.

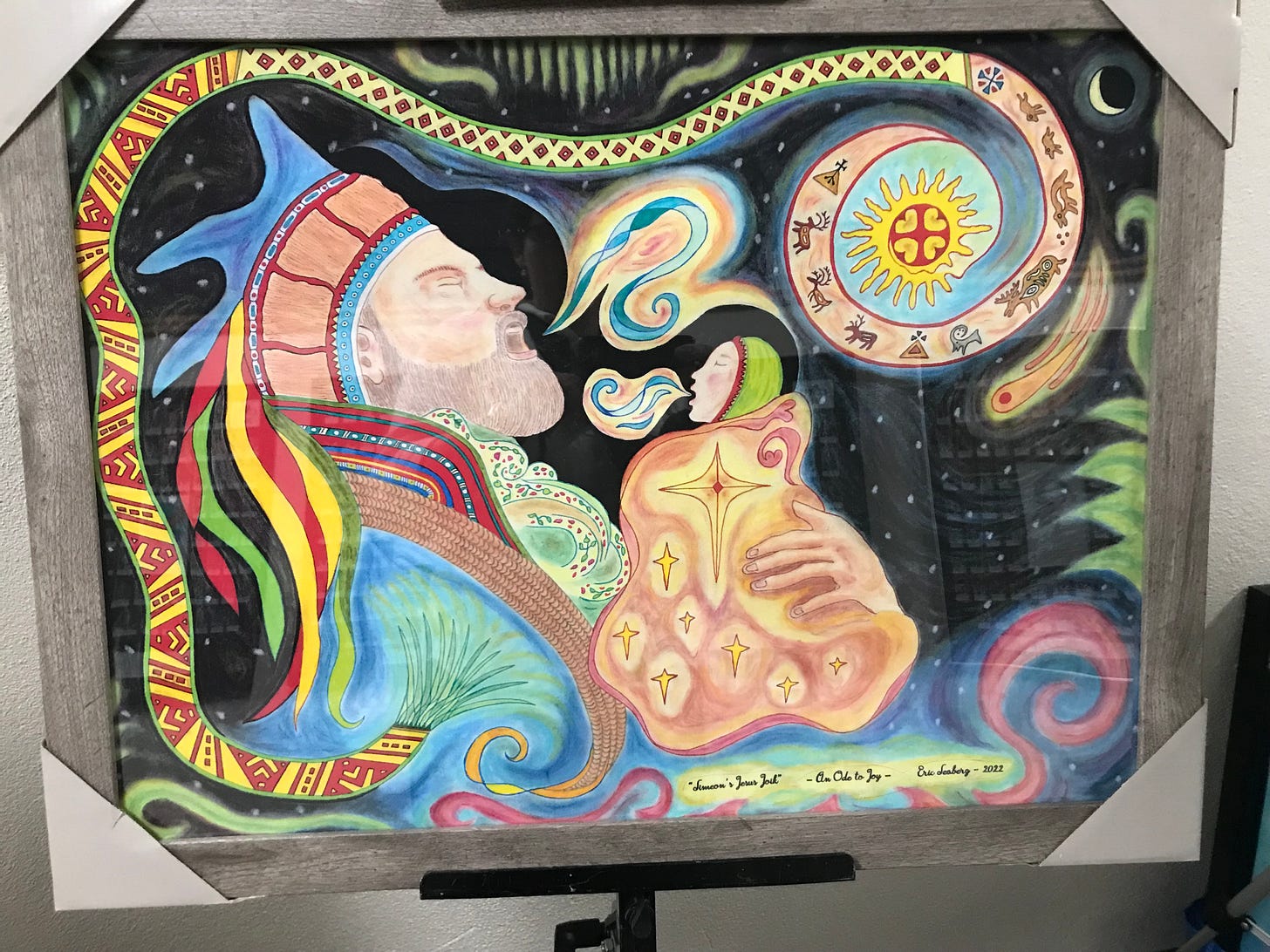

Painting by Eric Seaburg entitled “Simeon’s Jesus Joik”.

Eric is of Finnish descent and we have been on similar journeys in discovering our cultural heritage. Eric learned to joik a number of decades ago. He imagines Simeon in this painting, not as a Jew but as a Sami man welcoming and blessing the child Jesus. A joik is a form of singing, a combination of a yodel and Inuit throat singing. You can hear an example here.

As I look at this painting, the rich, vibrant colours, the embroidery on the clothing, and the head-back-unrestrained singing this does not feel familiar. I spoke with my mother about whether these things resonated with her, she exclaims emphatically that her grandmother never would have permitted such a gaudy display. The influence of a very austere religious sect to which my extended family belonged forbade ornamentation of any sort, not to mention the sensuality of this kind of singing.

I grieve this. Deep down, I know whose “own” I am. I belong to Christ and am a part of a new family. I belong to chosen family and to my blood family in deep and profound ways. But I mourn that there is something of God’s own image that I think is uniquely demonstrated in all the diversity of the Peoples of the earth. It saddens me that in the name of the God whose image we bear, there has been a scrubbing off of distinction.

We are better together. And each one has something to contribute to make the bond stronger. In the exchange of cultures and identities, we become more than the sum of our parts. In being God’s “own,” are we not brought all the more fully into our uniqueness? Knowing we are held together in love, are we not better able to hold difference?

I will probably never pick up the embroidery of my ancestors. But maybe I can contribute a joik to the joyous ingathering of the saints in the throne room of the Lamb.