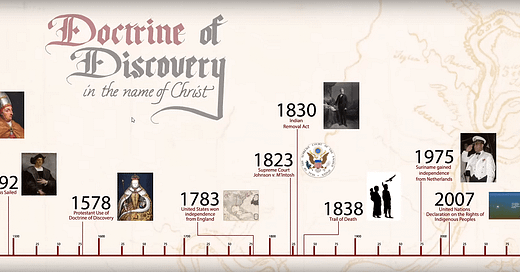

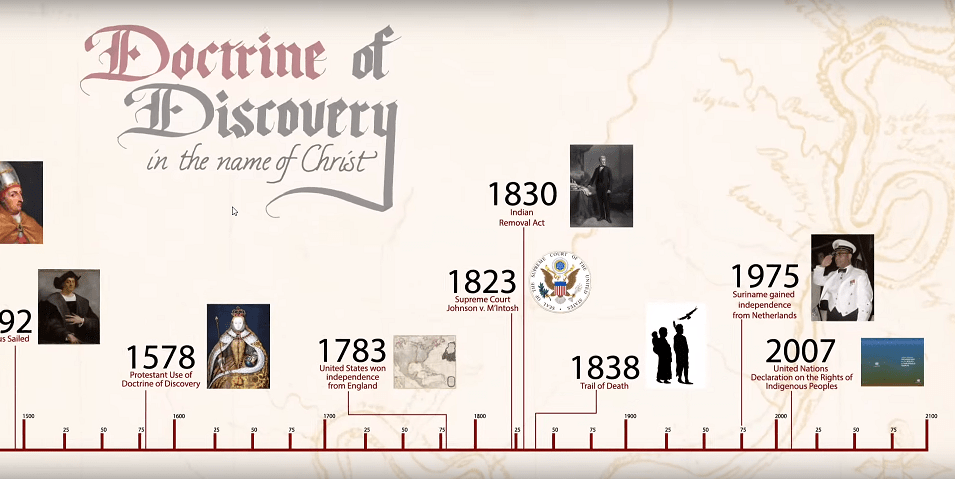

Over the next three weeks, I will discuss the Doctrine of Discovery, its history, and why it matters today. It is good to have you here.

Why Doctrine of Discovery Now?

In the 94 Calls to Action issued by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) at the end of the Canadian TRC on Indian Residential Schools, the Commissioners asked Christian faith communities, the pope, and federal, provincial, and territorial governments to repudiate the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius (empty lands), which were concepts used to justify European sovereignty over Indigenous lands and Peoples.

Despite the fact that these documents of the Catholic church were written in the 15th c., the TRC Commissioners felt that addressing them was vital for national healing. They saw the connection between these concepts and the establishment and abuses of Indian Residential Schools for 150 years. And they understood the ongoing systemic racism that continues to persist in Canada was built on the same foundation. Without dismantling these concepts, pulling them out by the roots, the Commissioners felt that the country’s ability to move forward would be inhibited. So, here we are, trying to learn about these ancient concepts with deep roots to better understand this land and our relationships with it.

Historical Background for the Doctrine of Discovery

Although we use a shorthand of speaking of the Doctrine of Discovery as if it were a single document, it is not. What we now refer to in this way is a series of papal bulls, which are a kind of position paper that popes regularly issue on a range of topics. So here is the run down of the particular popes and the particular papal bulls we are referring to in the Doctrine of Discovery.

In 1447, the Italian theologian Tommaso Parentucelli was elected Pope and adopted the name Nicholas V. In 1452 (four decades before another Italian, Columbus, “sailed the ocean blue”), Nicholas V issued Dum Diversas, a papal bull that established the framework for the Spanish Inquisition in Europe. Dum Diversas also gave theological justification for initiating the slave trade by creating categories that identified any non-Christian as an enemy of Christ, thereby establishing different consequences for murdering or abusing a non-Christian than a Christian. Dum Diversas also granted European rulers “full and free permission to invade, search out, capture and subjugate the Saracenes [Muslims], pagans and any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ.”[1]

In 1455, Dum Diversas was expanded through Rominous Pontifax, another papal bull that gave European rulers the right to confiscate: “The kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions and all moveable and unmovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them [Saracens, pagans, and other unbelievers] and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to convert them to his [the European king’s] use and profit.”[2] Pope Nicholas V saw these declarations as part of his evangelistic duty to “bring the sheep entrusted to him by God into the divine fold” so that he might “acquire for them the reward of their eternal felicity and obtain pardon for the souls.”[3]

In 1493, a new Pope, Alexander VI, issued InterCaetera, an edict that outlined a theological justification for the explorations of Christopher Columbus (whose name literally means, “Christ the Colonizer”). This papal bull implored Columbus to “bring under your sway the said mainlands, and islands with their residents and inhabitants and to bring them into the Catholic faith . . . to lead the peoples dwelling in those islands and countries to embrace the Christian religion.”[4]

Later papal bulls outlined the steps of conversion: “if they have written language persuade them by reason. With no written language, compel them by the sword. If they will still not be persuaded, then they have no soul and can be put to death with impunity.”[5]

The Social Impact of the Doctrine of Discovery

In systems theory, an institution (such as the Catholic Church) can issue policies or statements (such as papal bulls), and eventually, they can become internalized in society. Over time, these principles and ideas can even begin to operate apart from the institution. Such was the case with the Doctrine of Discovery, originally a set of church documents, but later adopted into the attitudes and actions of many other structures (like law) and societal attitudes in genera.

To give a specific example, Dum Diversas, Rominous Pontifax, InterCaetera, and subsequent papal bulls all instructed European explorers to believe that the Indigenous People they were encountering in the lands they visited were not fully human. Consequently, the land was not being put to “civilized” use. This way of thinking not only cleared European consciences at the time, but it also paved the way for more contemporary assumptions that we might hear expressed in Canada today. For instance, someone might argue that the government should be the ones to manage Crown land because Indigenous People would not have the knowledge and understanding to manage the land well.[7] This understanding of land as terra nullius (literally, “empty land”) was the basis for the creation of Crown land.

It is important to understand that these systemic ways of thinking benefited the imperial powers as they were seeking to move into new lands in order to extend their colonial influence. These new rules of engagement and attitudes about European and Christian superiority became policies upon which systems of governance were built. For example, in the Canadian context, newcomers adopted the Latin idea that European explorers or Christian missionaries could claim land pro Deo et patria, or “for God and country.”[8] This declaration was all that was required to make such a land claim “legally” true in the exported European systems of government, even though these lands had already been inhabited and governed by different sets of laws and customs.

This policy of determining whether or not the “pagans” encountered in these so-called “new” lands had souls persisted long past the influence of Catholic Popes, and thus it moved from being an institutionalized attitude to one that was internalized in the colonial culture. We see this way of thinking expressed in policies that limited the right of the First Peoples to claim land or to be identified as Christians, according to the European understanding.

In The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race, American author and theologian Willie James Jennings argues that the internalization of such oppressive attitudes has resulted in a diseased theological and social imagination.

Although no one today would say, “only Christians should own land.” There are more subtle ways that this attitude persists. There are judgments about reserve land and perceptions of it being “run down” as being an indictment of the moral failings of the people living (Indigenous People) there rather than the slum lords who have responsibility for housing on the reserve (the federal government). I regularly encounter some form of the question, “If we were to challenge the concept of Crown land and were to give some or all of it to the keeping of Indigenous Nations, how would they know how to take care of it?” This attitude, of course, assumes that those who have been stewards of these lands since time immemorial would need to be taught the “proper/civilized” way of understanding land as a commodity rather than the idea that perhaps Settler Peoples need to learn from Indigenous folks how to be good relatives with the land. Extraction and wealth are valued above relationship and reciprocity. What are other ways this diseased social and theological imagination has impacted how we see and understand the land?

Next week we will turn to the call to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery and what that could look like.

For more background check out this post from last year about the pope’s visit to Canada and its implications:

Ancient Debate Finally Resolved

An ancient unresolved debate from the 15th century that was recently resolved in the sky.

[1] Nicholas V, Dum Diversas, encyclical letter, Vatican website, June 1452, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/nichol05/dumdiversas-pontifex.htm

[2] Nicholas V, Romanus Pontifax, encyclical letter, Vatican website, January 8, 1455, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/nichol05/romanus-pontifex.htm

[3] Nicholas V, Romanus Pontifax.

[4] Alexander VI, InterCaetera, encyclical letter, Vatican website, May 4, 1493, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/alex06/alex06inter.htm

[5] As cited by Mark Charles, Unsettling Truths,20.

[7] Supreme Court of Canada, Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, Case no. 34986, 26 June 2014, https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14246/index.do.

[8] This idea was adopted in military contexts and remains the motto of the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps and the American Legion.